How to Bake Pi - Review

Summary

How to Bake Pi: an Edible Exploration of the Mathematics of Mathematics explores what mathematics is about by explaining the purpose and building blocks of mathematics in an easy-to-read language, drawing examples from everyday life, including baking.

I recommend it to you if you have never learned abstract mathematics but would like an introduction to it written in a way that even normal human beings can understand.

I do not recommend this book if you want to learn category theory or its application to software development. This book will give you an overview of what category theory is about, but will not teach you anything in depth about category theory. In terms of category theory textbook, the contents of this book would fit in as an extended introduction chapter.

What Makes It Special

Baking and mathematics are an odd combination to say the least. Eugenia Chang, the author, does her best to introduce mathematical concepts by making an analogy to baking. For example, when talking about abstraction, she takes mayonnaise and Hollandaise sauce as examples. Both are made with almost identical ingredients and processes, except that mayonnaise uses olive oil and Hollaindaise sauce uses butter. They are examples of “things that are somehow the same apart from small details,” which is how she describes abstraction.

Although analogy to baking is continuously made throughout the book, it is not the only analogy she uses. She also draws plenty of other examples from everyday life. In the chapter about abstraction, she uses following examples to make her point: recipes for different types of pies, numbers, heartbreaks, road signs, mathematical symbols, Google maps, and so on. It’s an odd collection, but the author clearly points out that they all are abstraction of some sort.

Sometimes the analogies feel a bit tenuous, and, due to their inherent limitations, they cannot provide precise definitions of the concepts that they try to illustrate. But the goal of the author is to make math easier to approach, and to help readers gain personal understanding or “illumination”, as she calls it, about mathematics. That’s why she came up with a lot of analogies instead of lazily throwing mathematical proofs at the readers. And she does a marvelous job at making this book an enjoyable read.

Motivation and Expectations

Ever since learning Haskell, and coming across odd terms like monoid, functor, monad, and others used in Haskell, I naturally got curious about what they actually meant. I learned that they were concepts borrowed from category theory, a branch of abstract mathematics. That was as far as I was willing to go at the time, but I’ve been looking for an opportunity to learn more about the subject since then. So when I heard that there was an easy-to-read introduction to category theory, I was immediately intrigued and bought the book. I was hoping for an introduction to category theory and some explanations on what those jargons in Haskell meant. I could accomplish the first goal, but not the second.

What Mathematics Is About

The title of the first part of the book is PART I: MATH. What

a straightforward title. Although I’m not terrified of math, I’m not in love

with it either.

I have learned mathematics in high school and college, but it was all about equations and theorems. Usually I would get a new equation from teachers or books, some explanations about what it does, some examples of its applications, and a bunch of exercises. There was almost no discussion about why I should learn this weird equation, or how is the topic related to something else that I’ve learned in the previous year. I suspect that most people have similar experiences regarding mathematics.

This book does none of that. Instead, it talks about principles and fundamental concepts of mathematics used for constructing those equations and theorems. The author defines that “mathematics is the study of anything that obeys the rules of logic, using the rules of logic,” and introduces core concepts of mathematics to flesh out that concise definition.

Abstraction is a technique for stripping away unnecessary details from things that we are dealing with, because those details hinder us from focusing on the essential properties of things and from applying the rules of logic to them. Number is an excellent example. When you want to know the total count of items in your grocery bag, you abstract away what those items are and just focus on the fact that there exists an item. For counting, that’s the right level of abstraction.

Then the author talks about principles and processes, which correspond to “the rules of logic.” These chapters emphasize that there are principles in math that are always right as long as they are examined under certain constraints, and that following correct process is often as important as getting the right answer.

Then comes the chapter about generalization, the centerpiece of the first part of this book. The author describes generalization as a process of gradually relaxing conditions for a concept in order to allow more things in. For example, a square has four sides of same length and four angles of same degree. When you slightly relax the condition about identical angles and require only the facing angles to be identical, you get a rhombus, which is a generalization of a square. Likewise, a parallelogram has more relaxed conditions than a rhombus, since only the facing sides need to have identical lengths. So it is a generalization of a rhombus.

Now we have a mental framework for understanding what mathematics is about. Mathematics is about studying abstractions of real things, each of which obeys certain principles and axioms. We can relax or tighten these principles to generalize abstractions in order to move around different levels of abstractions and study them in relation to one another.

Well, I’ve never heard mathematics described like that. As I’ve already mentioned, mathematics was just a collection of grueling mechanical techniques to me. In contrast, according to the author’s description, math sounds more like a fun meta-game where I could play around with the rules of another game.

Only after I’ve read the second part of the book did I realize that this is exactly how a category theorist would characterize mathematics. So the author is introducing category theory in a sneaky way while explaining fundamental concepts of mathematics. It’s quite clever.

What Category Theory Is About

The title of the second part of the book is PART II: CATEGORY THEORY. The

author does like her terse, straightforward titles.

This is how she explains what category theory is:

Category theory is mathematics of mathematics. […] It’s a sort of meta-mathematics, like Lego Lego. […] It works by abstraction of mathematical things, it seeks to study the principles and processes behind mathematics, and it seeks to axiomatize and generalize those things.

I think I could also write it this way: when you recursively apply to mathematics its own methodologies, you get category theory.

In part 2, the author explains what kinds of concepts are given importance in category theory in order to better explain her description of category theory.

In the chapter about context, she writes that “category theory seeks to emphasize the context in which things are studied rather than the absolute characteristics of the things themselves.” For example, number 5 is a prime number in the context of natural numbers. In the context of rational numbers, however, 5 can be divided by all kinds of numbers, not just 1 and 5, so it is no longer a prime number. So characteristics of number 5 depend on the context under which it is examined.

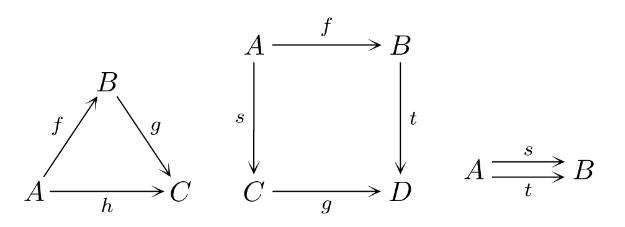

She also writes that “Instead of just studying objects and their characteristics by themselves, [category theory] emphasizes their relationships with other objects as the main way of placing them in context.” This is easier to understand with a diagram.

So the relationships like f, g, h are important subject of study in category

theory. If you think these relationships, called “morphism” or “arrow” in

category theory, look similar to functions, then you are not wrong. Function is

a kind of morphism and its mathematical notation bears some similarities to

that of morphism.

With all of those ideas laid out, the author finally gives the definition of

category. I will not discuss the definition in this post, but am presenting it

just for the sake of it. Even the author doesn’t really go into much detail

about this definition in the book. I think she too was presenting it just to

show what it looks like in formal notations, and nothing more. I will use .

to denote composition like in Haskell style.

Morphisms of a cateogry for some objects should obey the following rules:

- Given arrows

f(a) = bandg(b) = c, it has to result in a composite arrowg . f(a) = c. - There should be an identity arrow

i(a) = afor all objects, which means that for all other arrowsf,f . i = fandi . f = fshould hold true. - Given three arrows

f, g, h,(h . g) . f = h . (g. f)should hold true for all composite arrows.

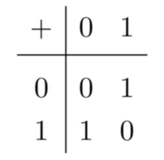

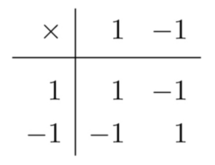

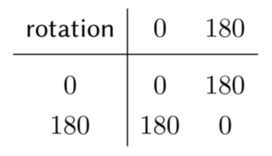

In the following chapter, she talks about how category theory studies structures arising out of morphisms. There are different objects whose relationships have very similar structures when laid out in diagrams. Here are three of the examples presented in the book: addition modulo 2, multplication of 1 and -1, and rotation by degrees.

The last few chapters discuss a few more topics of interest such as sameness or universal properties. They revolve around demonstrating how category theory studies these concepts, which have different meanings depending on the contexts under which they are examined.

So that concludes my not-so-brief overview of the book. Unfortunately, that’s where the book ends. So the book doesn’t really get into category theory - it just introduces it.

Other Musings

The author brings up some interesting ideas that are somewhat tangentially related to mathematics. For example, she says that math is easy compared to life, because math abstracts away illogical things in real life; and people find it difficult because they do not learn what it is for or because they are not interested in what math simplifies from real life.

That comment resonated with me. While learning math, I often wondered “why am I even learning this.” I’m sure most of you have similar experiences. I was never told why I had to learn imaginary numbers. And I was not interested in studying things like matrices because I could not see where I would use it. So think that her claim that math is difficult because it’s taught in a terrible way does make some sense.

I also noticed how abstract mathematics sounds very similar to philosophy. She talks about limitations of logic, and difference between knowing, understanding, and believing something. These topics are also commonly discussed in philosophy. I did hear that the two fields are similar in a lot of ways, but this was the first time that I actually saw that.

In addition, although I couldn’t learn anything about category theory in the context of software development, I do feel much more comfortable about terms like monads or functors now. Whereas they felt like some alien concepts out of nowhere, now I can place them in a context where they are just regular concepts, and know where to learn more about them.

Further Reading

While reading this book, I learned of another resource that could be helpful in learning about category theory in the context of software development. It’s called Category Theory for Programmers. I put it in my reading list.